Energy Performance Contracting (EPC)

Description

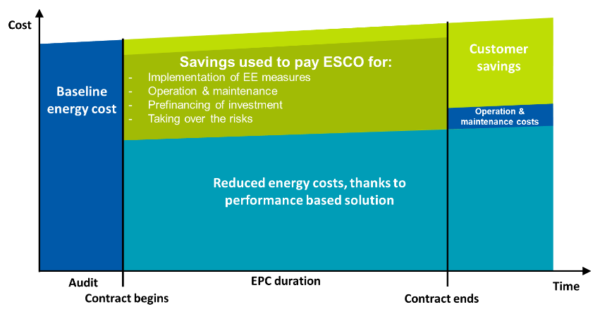

The EPC model is based on delivering energy savings compared to a predefined baseline. In this model, an Energy Service Company (ESCO) enters into arrangements with property-owners to improve energy efficiency of their property by implementing various measures. The ESCO guarantees energy cost savings in comparison to a historical (or calculated) energy cost baseline. For its services and the savings guarantee, the ESCO receives performance-based remuneration in relation to the savings it achieves. Generally, savings achieved can only be measured indirectly as difference between consumption before and after implementation of the energy efficiency (EE) and renewable energy (RE) measures (relative measurement: savings = baseline – ex post-consumption).

Most EPC projects focus on the implementation of energy efficiency measures (lighting, HVAC, energy management and control, envelope insulation). EPC models run under long-term contracts of typically ten years, depending on the payback time of the energy savings measures and the specification of the building owner (i.e. they may last up to 15 years when they include long payback-period investments such as wall insulation or window replacements).

Recommendations for replication

The main advantage of this Business Model is that it overcomes the main obstacle that limits energy refurbishments in case of multi-family buildings, namely the high initial investment costs.

In light of the business cases analyzed, the important elements in order to ensure the success of this business model in the residential sector are:

- Presence of regulations encouraging, if not even imposing, the heat metering in condominiums with centralized systems.

- High energy consumption and costs: Several sources state that EPC provided by ‘traditional’ ESCOs are only suitable for large projects (with a minimum energy cost baseline of around 200,000€/year). This requires clustering several multi-apartment buildings to achieve a significant number of dwellings. However alternative models, developed by smaller players, can be developed for single house or small condominiums.

- High share of occupant-owner (or one single owner, as in the case of social housing)

- Regulatory flexibility, allowing the application of the mechanism also in the case of tenant occupied apartments

- Presence of incentives, in the form of subsidies, even if the investments are borne by ESCOs.

- Low interest rates

- Access to third party financing (TPF) for small ESCOS: Small ESCOs (SMES) could open the EPC offer to single houses and small condominiums. However borrowing for ESCOs requires a credit history, which hinders the access of SMEs and small structures to finance. Facilitating the access of small ESCOs to TPF would alleviate this barrier.

"What” (value proposition)

The ESCO provides a customized service package, which includes design, installation, (co-) financing, operation & maintenance, optimization, user motivation.

For many customers financing is the most attractive part of EPC services for buildings. Key benefits include risk transfer, the ability to modernise a building’s energy infrastructure without necessarily having the funds and accessing external expertise, and the guarantee of performance. The key focus is on saving energy at the point of use first, before optimizing the supply of that energy.

"Who” (target customer)

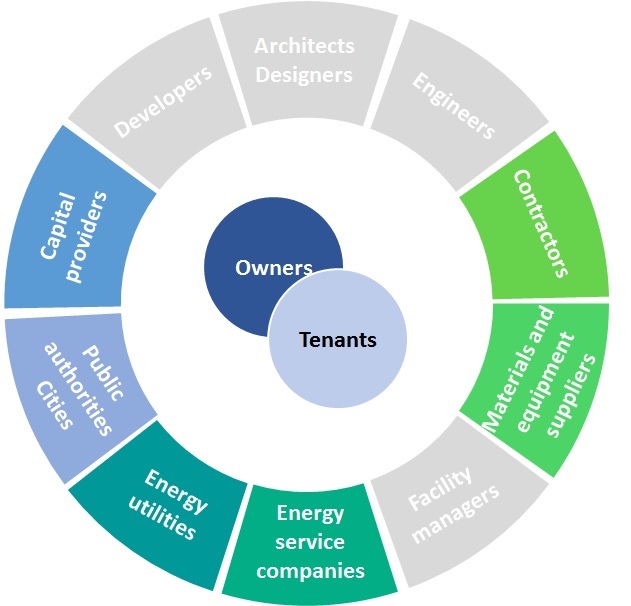

EPCs are mostly found in the public sector (for e.g. universities, hospitals, swimming & leisure facilities) and to a lesser extent in the industrial and commercial building sectors. This is because a large project is a prerequisite (the minimum energy cost baselines are usually at 200,000 €/year). EPCs have also been trialled for large residential building blocks.

"How” (value chain, activities, resources)

The ESCO acts as a general contractor and is responsible for the implementation and operation of the energy efficiency package at its own expenses and risk, according to the project specific requirements defined by the client and the ESCO. Purchasing of final energy (electricity, fuels) usually remains with the building owner.

ESCOs can also finance or arrange financing for the operation (with a third-party financier), and their remuneration is directly linked to the demonstrated performance regarding the level of energy savings or energy service. Finally, to ensure that the building is used in the most efficient way, building occupants receive training on energy efficiency practices.

When the client is from the public sector, EPC are usually provided as a Public Private Partnership.

"Why” (revenue model and cost structure)

Cost structure: Costs for the ESCO include the implementation of the EE/RES measures, their operation & maintenance, pre-financing of the investment and taking over risks according to the project specifications defined in the contract. Transaction, measurement and verification costs of EPC projects are high. Determining and adjusting the baseline is a crucial issue in the EPC business model (as it can generate a considerable degree of insecurity and monetary risks for the ESCO) and needs to be undertaken for all performance-based billing periods over the entire contract term.

Revenue stream:

In Energy Performance Contracting, the ESCO’s remuneration is performance based:

- it guarantees for the outcome and all-inclusive costs of the services

- it takes over commercial as well as technical and operational risks over the project term.

Two options exist: EPC with shared savings and EPC with guaranteed savings. In the first case, the ESCO shares an agreed percentage of the actual energy savings over a fixed period with the customer. An ESCO’s share of savings typically falls within a range from 50% to 90%, with 65% to 85% representing the most common range of values. In the second case, if the savings are less than expected, the ESCO covers the shortfall. If the savings are overachieved, the ESCO can recover the excess. After the end of the contract term, the facility owner benefits from the full energy cost savings, but all operation and maintenance expenses are on his accounts.

Related Case Study

Torrelago district

The renovation of Torrelago district was implemented in the framework of the FP7 funded CITyFiED project (http://www.cityfied.eu/) .

Torrelago district involves 31 private multi-property residential buildings (1488 dwellings) that were constructed in the 1970s–1980s, more than 140,000 m2 and 4000residents involved. Former conditions of the district were very low in terms of efficiency, comfort and costs, which fostered the intervention. Main energy measures implemented at the building scale are buildings external insulation (Composite System-ETICS, ventilated façade), connection to district heating (twelve new heat exchange substations at building level), individual metering to raise users’ awareness.

Related to the “standard envelope insultation – ‘deep’, with ETICS” (in the Renovation Hub: https://renovation-hub.eu/refurbishment-solutions/etics/).

A connection to district heating was also implemented