Business Models

What business models would suit you best?

The objective of this section of the Renovation Hub is to present the variety of Business Models that already exist to support energy renovation, guide you in this large collection to find the best “recipe”, provide recommendations for replication, and illustrate the application of most promising ones through Cases Studies.

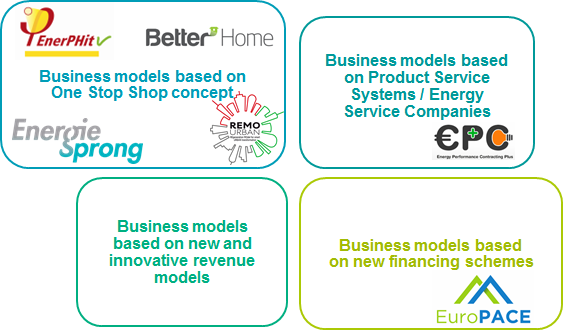

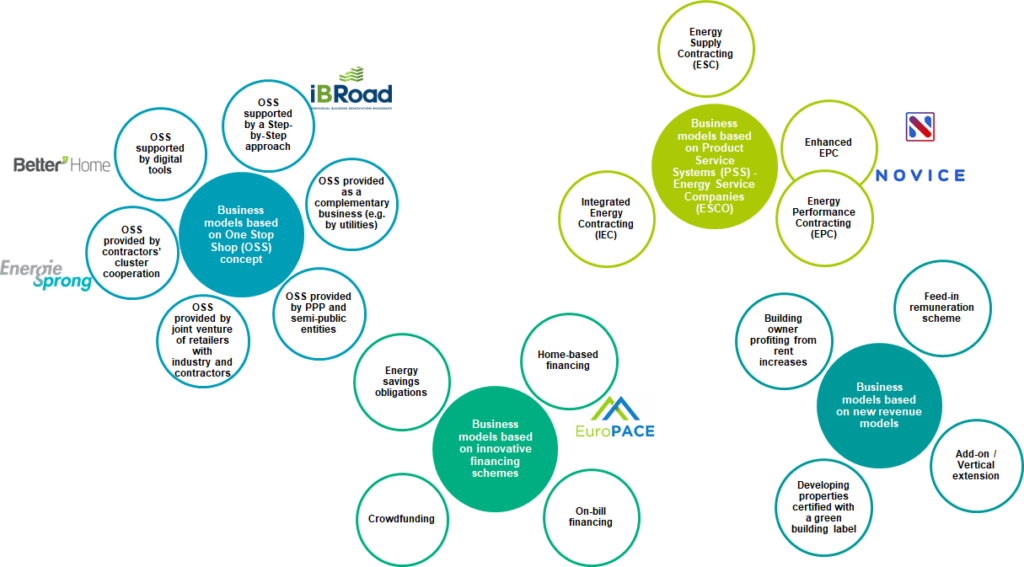

We have identified four main families of business models:

Real business models are often a combination of several business model patterns, and business model families should not be considered in isolation: on the contrary, combining several patterns can provide a more robust business model.

When setting up a renovation project, the chosen business model(s) should be tailored to the targeted market segment:

| For who? | The problem |

What? (Recommended Business Model) |

How? |

Can be combined with: | Where? (Example of countries with high potential for this BM) | |

| Type of dwelling | Type of owner | |||||

|

Owner occupant | Renovation journey too costly and complex for the home owner | One Stop Shop | Provided by PPP / semi-public entities | Countries with incentives for home owners to renovate | |

| Supported by a digital tool | Denmark, Germany | |||||

|

Social housing | Renovation in occupied dwellings. Acceptance by tenants | One-Stop-Shop “Energiesprong” | Initiated by a dedicated marketing team | Add-on business model | Netherland, Denmark, Germany, UK |

| Energy Performance Contracting | Provided by an ESCO | Collective Self Consumption | France, Denmark | |||

|

Condominiums | Renovation in occupied dwellings. Acceptance by multiple owners. | One Stop Shop | Provided by semi-public entities | Step by Step approach | Germany, France, Denmark |

|

Public buildings | Upfront investment. Long term estate management | Energy Performance Contracting | Provided by an ESCO | Crowdfunding (for cultural heritage) | France, Denmark |

|

Offices and other tertiary buildings | Attractivity of estates for companies / lessees | Energy Performance Contracting | Provided by an ESCO | France, Denmark | |

Other types of Business Models you may be interested in:

Other One-Stop-Shops

- OSS provided as a complementary business (e.g. by utilities, insurances)

- OSS provided by joint venture of retailers with industry and contractors

- OSS provided by SME contractors’ cluster cooperation

- OSS with home-based financing

Energy as a service:

New and innovative revenue models

New financing schemes

Each Business Model presentation is structured in four blocks: What? Who? How? Why?

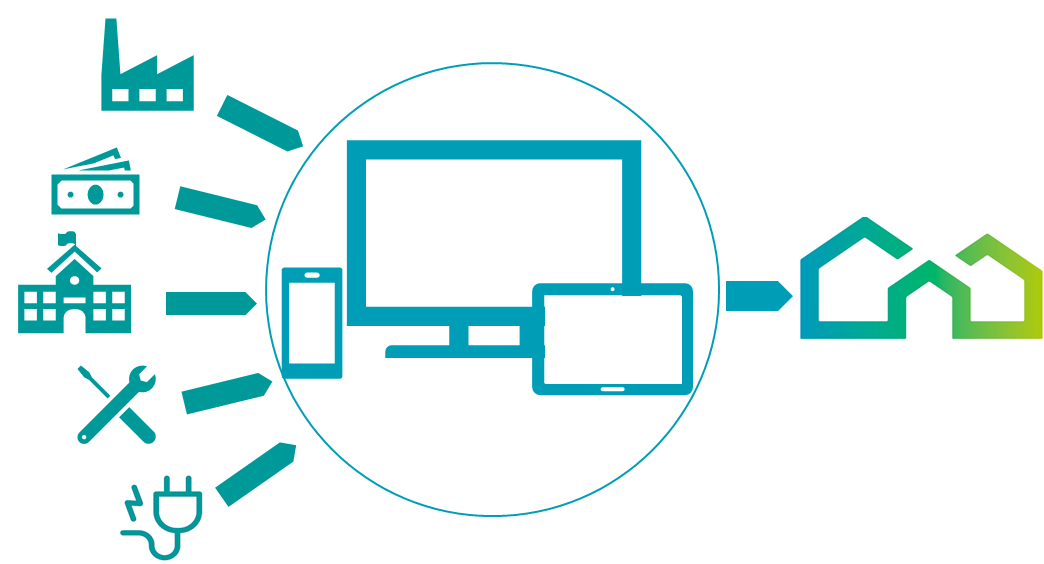

One-Stop-Shop supported by digital tools

In this business model the key player is supported by digital tools guiding home-owners as well as designers (or contractors) in the initial planning of the renovation work. The tool usually acts as a guide to optimize the application of the overall retrofitting process by for example collecting all the information related to the initial state of the building to be renovated and the preferences, the needs and desiderata of the building owner. The ICT tool processes the information gathered and suggests an optimised approach to the renovation project.

The main advantage is the possibility to effectively manage the whole process in a comprehensive way. As the idea is very much based on creation and availability of process descriptions, checklists and tools, the maintenance and update of the material are key. It is also highly important to be able to create reliable initial information about the building stock and provide robust initial model. In order to make reliable assessment about the saving potentials in terms of energy and costs, the actors involved must be able to use appropriately the tools for energy performance assessment and be able to make justified conclusions about the savings. Here the quality of the initial information is highly important. In addition, a solid understanding of the users’ behaviour and willingness to commit to energy savings is essential.

An example of this business model is BetterHome in Denmark, an industry-driven one-stop-shop model, which has proven successful in boosting demand for holistic energy renovations in Denmark, since the model was launched in 2014. It was profitable after just three years, with 200 projects in 2016 and is expected to continue its growth. Understanding that renovating a building is a big commitment, this model creates a burden-free experience for the building owner and offers a service that goes beyond replacing building components. The home-owner-centric renovation journey has two main mechanisms: structuring the process for the installers and increasing building owners’ awareness.

Recommendations for replication

While the central aspects of the renovation journey are replicable on most European markets, the model must be adapted to the local context. Applying a similar model in other countries will require a greater focus on quality assurance and an integration of financial support into the model. In Denmark, quality assurance is heavily regulated, including guarantees for the building owners. A more comprehensive quality and compliance scheme is required on most of the other European markets. Furthermore, the available financial subsidy scheme for energy renovations in Denmark is modest and rarely decisive for the building owners’ decision to invest. In countries with substantial public support schemes for energy renovations, this can be incorporated into the business model.

Key factors for replication are:

- Use digital solutions to bring added value to the end-users: BetterHome shows that digital solutions can help the construction industry become more consumer-centric and service oriented. Moreover, with the use of innovative digital tools, building professionals can provide a smoother process, for themselves and for the building owner. Aligning with existing stakeholders on the market, including banks and mortgage providers, creates a constructive win-win situation.

- Structure the supply-side: The success of the home-owner-centric business model can be explained by the advanced service-oriented role of the installers. BetterHome trains and guides the installers on how to approach the home-owner, from the first contact to the finalisation of the process. In support, BetterHome also simplifies and structures the renovation process for the installer, through supportive and innovative digital tools, enabling a better evolution for all involved.

- Build awareness for the end-users: Training the installers in order to sell the broader picture, including benefits (e.g. low interest rates, increase in property value, improvements to health of their children and comfort, as well as climate and environmental benefits). The installer is not just replacing the old building elements, but creating a better living environment.

- Safeguard the good reputation: In Denmark, the four companies behind BetterHome are highly respected and associated with quality. Through the cooperation in BetterHome, the companies have worked together to also raise the reputation of the installers.

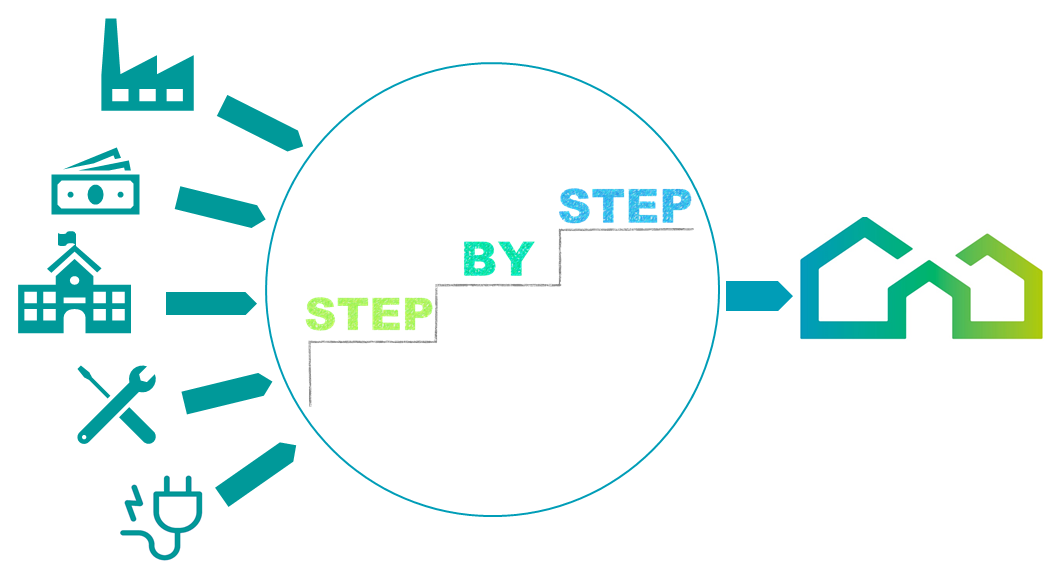

One-Stop-Shop supported by a Step-by-Step approach

The Step-by-Step renovation model is a widely diffused model of building refurbishment that consists in the replacement of different building components (such as windows, plasterwork, roof covering, boiler etc.) according to their life duration.

One of the benefits of such an approach is that it gets the most out of each building component so that the initial investment is taken advantage of to its fullest. The need for replacements of various components arises at different points in time which means that in the case of a complete building retrofit, components that are still intact are renewed unnecessarily before their due time, leading to sub-optimal investments. With the step-by-step approach this can be avoided. When applying this approach, a building renovation plan should be made for all measures, including those which lie in the distant future, before starting the work. In this way, it can be ensured that an optimal end result is achieved in terms of cost-effectiveness, energy efficiency and quality.

Recommendations for replication

The step-by-step approach is probably the most likely to be replicated as it minimises the main obstacle to the process of energy renovation of buildings, i.e. the high initial investment. It is the approach that is most suitable for small investors with a prudent attitude, who aim to improve their living conditions and who do not immediately seek a significant increase in property value.

The main advantage lies in the possibility to check, after each intervention, the benefits in terms of comfort and energy savings, splitting the risk between smaller investments, as well as keeping the possibility to make corrections in the course of future interventions.

The important elements for the success of this business model are:

- Technical know-how of the OSS consultants who advise clients:The interventions carried out in the early stages will have to be compatible with the interventions planned in the future, possibly avoiding unnecessary redundancies, and therefore the allocation of costs in interventions that will not generate savings.

- High percentage of dwellings occupied by owners: Statistically, homeowners are more likely to carry out improvement works.

- Cumulation of incentives over time: In order not to decrease the interventions after the first one, it is essential that the incentives accrued during the various interventions are compatible and cumulative.

- Acceptable level of income and possibility to take advantage of incentives provided as tax deduction: As highlighted by Ameli & Brandt, 2015 the level of income is one of the parameters most closely related to the probability of investing in energy efficiency. Obviously, it has to be weighed against the cost of living, energy and, above all, the average cost of investment.

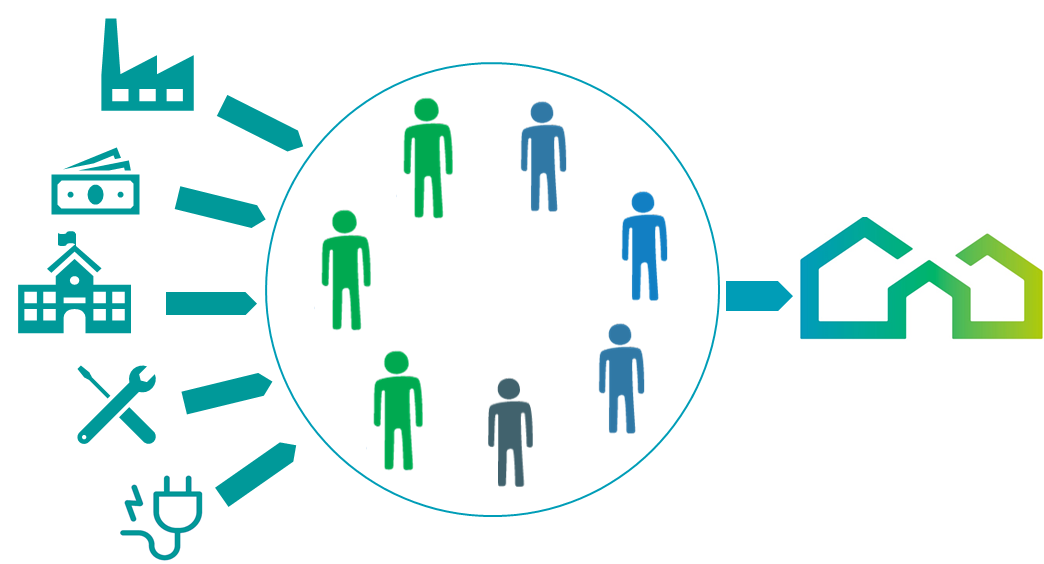

One-Stop-Shop provided by multi-disciplinary team

In this model the project is carried out by a multi-disciplinary team in a cooperative manner, consisting of partners with complementary competences, such as architects and designers, constructors, energy-efficiency experts, market and financial experts, technology suppliers, strategy and operations planners. Starting from the initial design phase, the team works together, in strict collaboration with the building owner, in order to select the optimal renovation measures to adopt, planning the whole renovation project according to customers’ needs.

The cross-fertilisation of gathering different actors together in an early phase of the renovation project permits to define a holistic approach to the renovation intervention. In this way sustainable and energy–efficient retrofitting solutions can be deployed, with an optimal control over the total costs of the renovation project and guaranteed efficiency performances.

A successful example of this business model is Energiesprong. Energiesprong is a whole house refurbishment and new built standard and funding approach. It originated in the Netherlands as a government-funded innovation programme and has set a new standard in this market. It is now being replicated in the UK, France, Germany and Italy.

Recommendations for replication

The key to success for the replicability of this business model is the identification of the market segment to focus on.

Building upon the lessons learnt from the Hem and Nottingham case studies, the important elements in order to ensure the success of this business model in the residential sector are:

- A wide availability of similar single or multi-family buildings, characterized by not overly complex geometries, that are in need of refurbishment.

- Limited segmentation of the building stock in order to be able to deliver standardized solutions

- A stable upward trend in real estate market prices that can drive this type of investment.

- High GDP per capita and low private debt, ensuring the existence of a demand segment capable of dealing with major investments and/or high disposable income in households, or to make it financially sustainable for private individuals to purchase refurbished apartments.

- Grants and tax incentives that can support this approach in areas with lower incomes.

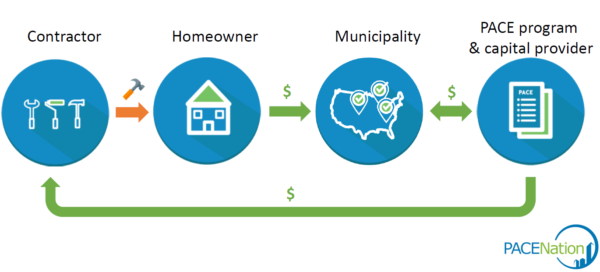

One-Stop-Shop with home-based financing

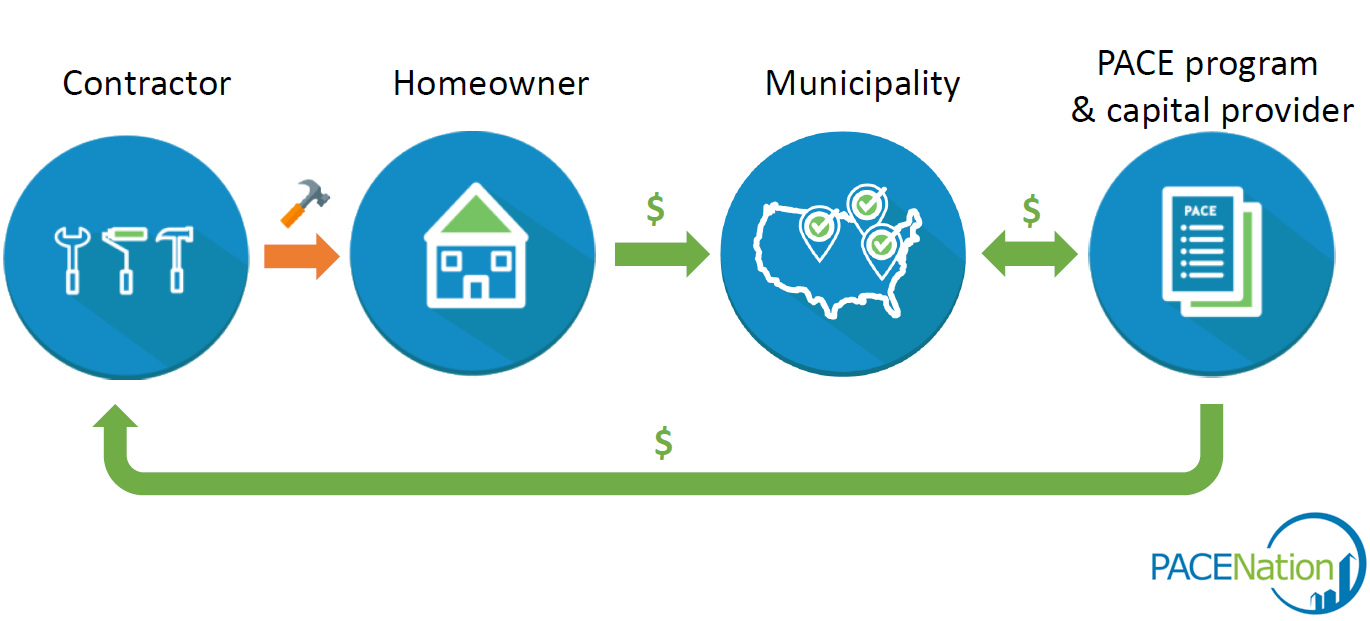

This business models took inspiration from the Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) concept, widely piloted in the US, where local governments issue bonds for renovation projects.

The building owner repays the loan through an additional special “assessment” payment on its property tax bill for a specified term. These “assessments” are comparable to loans as the property owner pays off its debt in instalments over a period of various years but from a legal point of view they are not considered as such.

When the property changes ownership, the remaining debt is transferred with the property to the new owner. In other words, PACE financing is a mechanism set up by a municipal government by which property owners finance energy efficiency and renewable energy measures via an additional tax on their property. The property owners repay the “assessment” over a period of 15 to 20 years through an increase in their property tax bills. In the US, property tax payments are made annually or in arrears but payment modalities may be different in other countries, especially in Europe.

The PACE concept is being adapted to Europe by the EUROPACE project. As in PACE, the innovative character of the EUROPACE mechanism is that financing is linked to the taxes paid on a property. In other words, the financing lent by a private investor is repaid through property taxes and other charges related to the buildings. The EUROPACE mechanism also sets up of One Stop Shop by engaging several stakeholders in the process: local government, investors, equipment installers, and homeowners.

Recommendations for replication

In the framework of the EUROPACE Project an in-depth analysis to assess the legal and fiscal readiness for the adoption of an on-tax financing mechanism across EU28 was developed. The main key factors are hereby reported.

The important elements for the success of this business model are:

- Suitability of the legal framework for on-tax financing: As EUROPACE is added to property taxes, the suitability of the legal framework is important an important factor to consider to assess the on-tax financing mechanism replicability. Property taxes differ in many aspects between countries but issues such as the existence of a property-related tax, the regular collection of property taxes, or a relatively low level of exceptions in the tax collection mechanism are essential for the legal implementation of this business model.

- Municipal capacity to develop an on-tax financing mechanism and municipalities’ experience and policy objectives concerning EE and/or climate mitigation: Municipalities play a vital role in the EUROPACE business model, as they have an interest in implementing EE solutions and are also relevant actors in the creation of private-public partnerships (PPPs). The experience of municipalities in working on comparable assignments and to estimate their readiness to implement EUROPACE, can be assessed referring mainly to municipalities’ capacities to manage EE projects, particularly in a PPP model. According to the best practices from PACE implementation in the US, a key indicator for replicability is a case where the municipality has experience working with the private sector to implement broadly defined investment programmes. Another key indicator for replicability is the existence of EE programmes and policies in buildings

- >Enforceability of local taxes and/or property taxes and assessment of charges, defaults, and delinquencies: The enforceability of local taxes and/or property taxes and an assessment of charges, defaults, and delinquencies assesses as well the roles and responsibilities of the local authorities that provide guarantees (including senior liens) to investors. In particular, this replicability indicator focuses on the progress made towards fair, standardised, and transparent administrative processes as well as possible penalties, tax liens, and, eventually, foreclosure procedures in cases of the non-payment of taxes. A fully developed guarantee mechanism over the payment of property taxes is considered as a key enabler.

- Political, institutional, and social perceptions and acceptance of EUROPACE: It is difficult to compare the attitude towards property taxes, as these vary significantly among the countries analysed. There is a vast set of secondary country-specific data on the impact local taxes have on elections and on local and national debate in general. While in some countries politicians barely mention the importance of local taxes, in other, increases in local taxes lead to mass protests and can determine the results of local (or central, if the government is fully in charge of local taxation) elections. In principle, it can be concluded that the more stable and institutionally continuous the tax is, the easier it will be to use it as a basis for EUROPACE implementation.

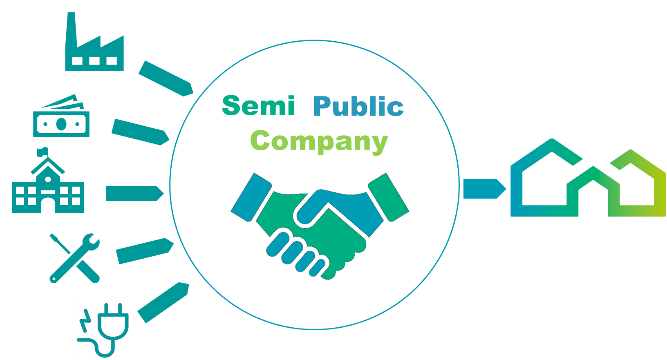

One-Stop-Shop provided by semi-public entities

The collaborative model presented hereafter differs from the traditional PPP model and presents the model of One Stop Shops provided by semi-public entities, where local authorities and private companies join forces to provide sustainable OSS structures – so called renovation platforms – to support the residential renovation market.

One-Stop-Shop provided as a complementary business (by e.g. utilities, insurances)

The One-Stop-Shop concept means that a single service provider is responsible for holistic renovation of the building as per the wishes of the building owners, including implementation of energy efficiency measures, or building internal renovation. Thus, the one-stop-shop model foresees that a single actor offers full-service holistic renovation packages including consulting, independent energy audit, renovation work, follow-up (independent quality control and commissioning) and financing.

Key actors that could develop a One-Stop-Shop Model for the renovation of existing buildings are real estate agencies, insurance companies and utilities. These key actors take advantage of their existing market position, to sell a complete package which they compose by using subcontractors to gather the right skills. The advantages and opportunities offered by the development of such a complete service package are:

- To enter a growing market (energy efficient renovation)

- To open new businesses thanks to the development of new partnerships with other companies

- To offer a clear and complete value proposition (and quotation) that fulfils the needs of the owner.

The first step to develop a new and innovative One-Stop-Shop business model is to understand the customers’ real needs. Regarding renovation, the building owner might not know precisely his own needs, as he may have limited knowledge about what can be done to the building in order to make it more energy efficient. The decision-making process is therefore a “learning process”. To guide him through this, credibility and trustworthiness is a prerequisite. As a consequence, the challenge is to create consortiums with a mixture of credibility, an existing market position, capacity and capability to supply a complete package of good quality. In the case of stakeholders that decided to expand their business into renovation as a complementary business, they shall involve directly the different trades (e.g. installers to change the heating system, carpenter to install windows, construction company to improve insulation and/or install windows, energy auditor to evaluate energy efficiency potential, and if relevant window/door supplier, insulation supplier, painters, heating system suppliers).

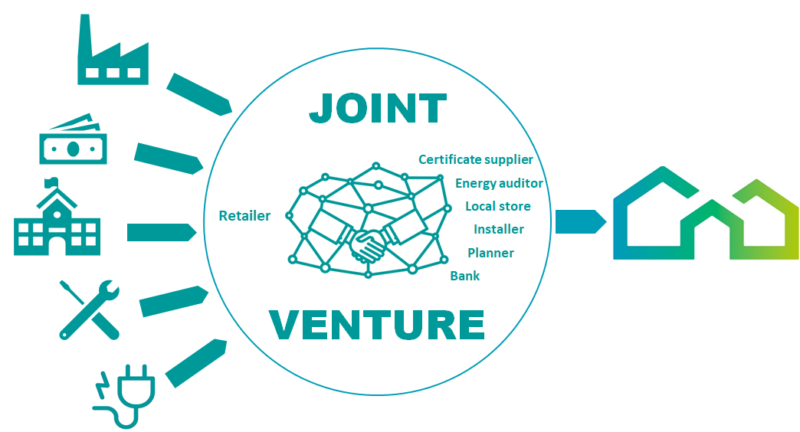

One-Stop-Shop provided by joint venture of retailers with industry and contractors

Creating a joint venture of retailers with industrials (materials and product manufacturers / suppliers) and contractors is a solution to set up a one-stop-shop model to refurbish existing buildings. Consortium of industrials with complementary products provides a full-service package.

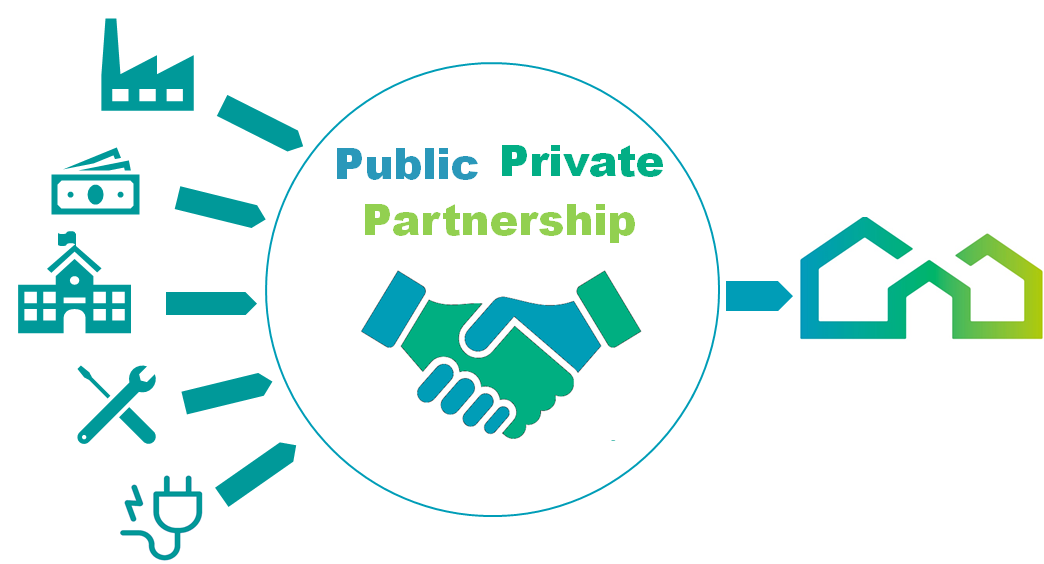

One-Stop-Shop provided by Public-Private-Partnership

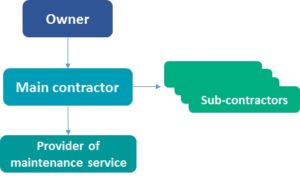

Public Private Partnerships (PPP) are a well-known delivery model in the construction sector, involving a contract between a public sector authority, the building owner, and a private contractor in charge of the management and the development of the building renovation project. The private party provides the service to the public authority, assuming substantial financial, technical and operational risks in the renovation project. This model is already widely used around the world, on a project basis, i.e. a new PPP is usually settled for each building (or set of buildings) to be renovated.

The Energy Performance Contracts (EPCs) where the public sector uses private energy service companies (ESCO) through Public Private Partnership arrangements, fits for instance in this category (more information can be found under the EPC description).

In this collaborative model, private and public partners collaborate coordinating their skills and knowledge for long term contracts (usually 20-30 years). The selected contractor involves designers, maintenance services providers and other subcontractors needed stipulating specific contracts with each of them, during the whole project duration, being the only contact point for the public building owner.

PPP models are mostly used in very complex projects that require high level of integration. Since PPP delivery method is widely used around the world, many types of financing contracts may be used under this scheme: usually, for instance, the PPP contractor finances the initial investment and the client pays a constant fee for using the property during the contract. In some cases, a private sector consortium may create a special company called a “special purpose vehicle” (SPV) to develop, build, maintain and operate the asset for the contracted period.

PPP models are mostly used in very complex projects that require high level of integration. Since PPP delivery method is widely used around the world, many types of financing contracts may be used under this scheme: usually, for instance, the PPP contractor finances the initial investment and the client pays a constant fee for using the property during the contract. In some cases, a private sector consortium may create a special company called a “special purpose vehicle” (SPV) to develop, build, maintain and operate the asset for the contracted period.

PPP model are usually implemented in the case of multidisciplinary projects where team members have to strongly collaborate. Because of the mix of responsibilities and finance schemes, PPP delivery models provide opportunities for both public and private sector. However, PPP are complicated delivery models in the construction sector that require strong involvement of the different stakeholders, therefore PPP delivery method may cause an increase in time and cost of projects delivery and increase potential risks associated to the different steps of development.

One-Stop-Shop provided by contractors’ cluster cooperation

In today’s construction industry a movement from conventional competition and contract models towards new partnership and collaborative business models can be observed. These partnership business models comprise management and manufacturing methods and correspond more to real businesses in the construction industry. This progress of the market within the construction sector leads to a usage of new business models also in order to overcome traditional price-driven competition towards a more collaborative working environment and a value-driven competition. Moreover, each large building retrofitting project needs slightly different business models according to building ownership, building typology, scope of the retrofitting, requirements, barriers such as available financing, actors engaged, guarantees, referenced projects, etc. The actors in the retrofitting project life cycle should be able to choose the optimal business model, and should be able to realise it (organisation, contracts, resources, knowledge, and technical competences). Solid and well-defined methodology and digital tools are needed for the project based on development and implementation of these novel business models. An individual SME is limited in many ways to reach these goals. The only solution is a collaborative, cluster or networked based approach.

In this context, it may happen that the service provider of the One-Stop-Shop business model is a team of contractors that may all be SMEs or with a major contractor and its affiliated partners. Small-medium sized construction companies may thus enter into partnerships with other actors such as suppliers of key components/material and architect/engineering company if these capabilities do not exist in house.

In case of SME cluster collaboration, generally, the SMEs scope, competences and resources are limited for developing large construction investments, for example large real-estate retrofitting projects. Mainly in the public sector, where the competition is based on the “lowest price” criterion, the SMEs have many difficulties to win the projects. An important opportunity is the adaptability and flexibility of SMEs to different contractual arrangements. This can be implemented only by a group of companies covering all required competences, in well-organised collaborative approach. The operation and maintenance organisation and end-users should be directly involved. These actors have key impact on high performing buildings (retrofitted buildings) and with that also on the overall outcome (economic, environmental, social) of the retrofitting project.

In this framework, SMEs operating in the construction field and in the same region may look for a holistic coverage of the construction industry market, applying business models which can be profitable by fulfilling a wide spectrum of clients’ requirements. Clusters of regionally active construction SMEs have an increasingly need to be organised into networks or strategic alliances. This will answer to the business opportunities, which require individual resources such as specific expertise, workforce or equipment. For widening the range of competences some of them enter even wider association such as e.g. German Facility Management Association (GEFMA).

Nevertheless it has to be underlined that when the client is from the public sector, it is necessary to define the leader of the SME cluster to be possible to contract projects. Definition of the leading SME partner can be a problem. Legal issues have to be cared about (contract forms, assurances in the case of SME bankruptcy, responsibilities and guarantees for longer time).

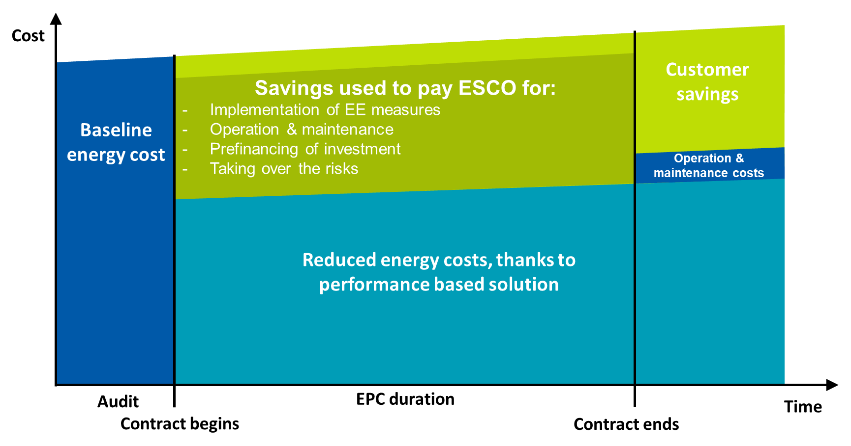

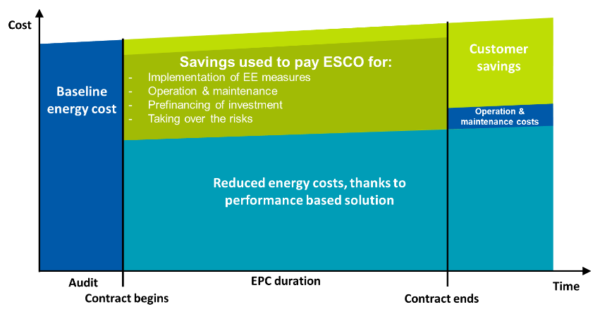

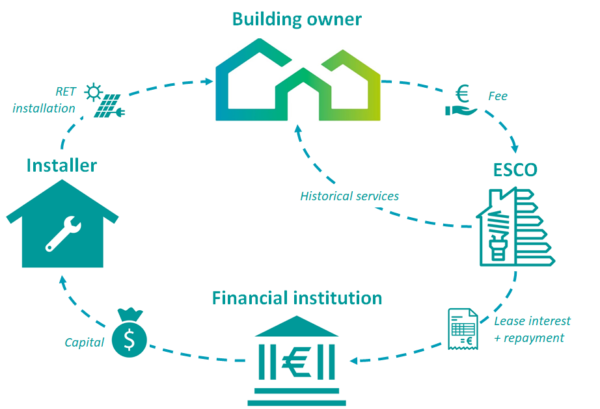

Energy Performance Contracting (EPC)

The EPC model is based on delivering energy savings compared to a predefined baseline. In this model, an Energy Service Company (ESCO) enters into arrangements with property-owners to improve energy efficiency of their property by implementing various measures. The ESCO guarantees energy cost savings in comparison to a historical (or calculated) energy cost baseline. For its services and the savings guarantee, the ESCO receives performance-based remuneration in relation to the savings it achieves. Generally, savings achieved can only be measured indirectly as difference between consumption before and after implementation of the energy efficiency (EE) and renewable energy (RE) measures (relative measurement: savings = baseline – ex post-consumption).

Most EPC projects focus on the implementation of energy efficiency measures (lighting, HVAC, energy management and control, envelope insulation). EPC models run under long-term contracts of typically ten years, depending on the payback time of the energy savings measures and the specification of the building owner (i.e. they may last up to 15 years when they include long payback-period investments such as wall insulation or window replacements).

Recommendations for replication

The main advantage of this Business Model is that it overcomes the main obstacle that limits energy refurbishments in case of multi-family buildings, namely the high initial investment costs.

In light of the business cases analyzed, the important elements in order to ensure the success of this business model in the residential sector are:

- Presence of regulations encouraging, if not even imposing, the heat metering in condominiums with centralized systems.

- High energy consumption and costs: Several sources state that EPC provided by ‘traditional’ ESCOs are only suitable for large projects (with a minimum energy cost baseline of around 200,000€/year). This requires clustering several multi-apartment buildings to achieve a significant number of dwellings. However alternative models, developed by smaller players, can be developed for single house or small condominiums.

- High share of occupant-owner (or one single owner, as in the case of social housing)

- Regulatory flexibility, allowing the application of the mechanism also in the case of tenant occupied apartments

- Presence of incentives, in the form of subsidies, even if the investments are borne by ESCOs.

- Low interest rates

- Access to third party financing (TPF) for small ESCOS: Small ESCOs (SMES) could open the EPC offer to single houses and small condominiums. However borrowing for ESCOs requires a credit history, which hinders the access of SMEs and small structures to finance. Facilitating the access of small ESCOs to TPF would alleviate this barrier.

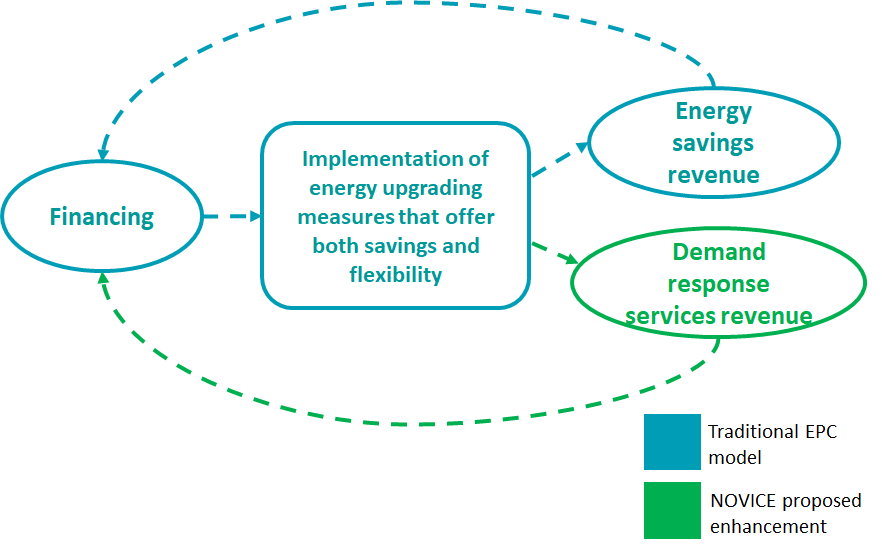

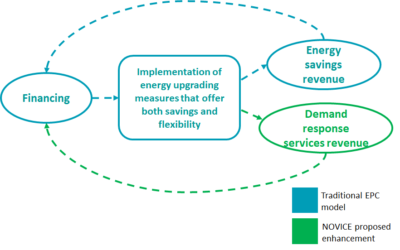

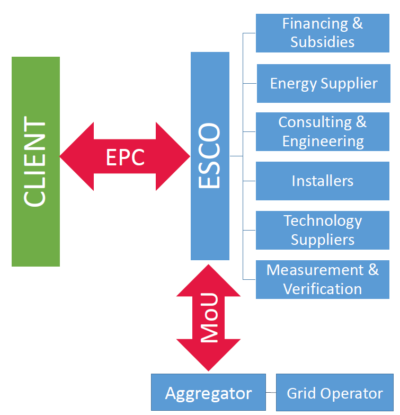

Enhanced Energy Performance Contracting

The Enhanced Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) model, proposed by NOVICE project, consists to generate revenues from Energy Savings, as in the classic EPC model, but also to generate revenues from Demand Response Services.

Demand response is a way of shifting or reducing electricity usage during peak periods. Indeed, when electricity demand exceeds supply on the grid, clients’ electrical asset consumption can be adjusted by using aggregator technology. Thanks to this shift, power returns to the grid and the supply and demand balance is restored in a cost effective and green way. Also, the clients earn revenues simply for participating and being available.

Demand response is a way of shifting or reducing electricity usage during peak periods. Indeed, when electricity demand exceeds supply on the grid, clients’ electrical asset consumption can be adjusted by using aggregator technology. Thanks to this shift, power returns to the grid and the supply and demand balance is restored in a cost effective and green way. Also, the clients earn revenues simply for participating and being available.

In the Enhanced EPC model, the ESCOs remain the single point of contact for all measures but uses the services of a demand response aggregator to provide services to the grid. A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) governs the relationship between ESCO and Aggregator.

Market readiness for Enhanced EPC is varying across European countries.

Some of them, like France or UK, have well developed or growing ESCO markets and several open DR markets with regulation that encourages aggregators to participate. Other countries (Belgium, Germany, Finland…) have either an advanced ESCO or an open DR market but strict regulations that limit the ability of aggregators to participate. Finally, some EU countries like Italy or Spain have immature ESCO and closed DR markets (or do not legally allow aggregation).

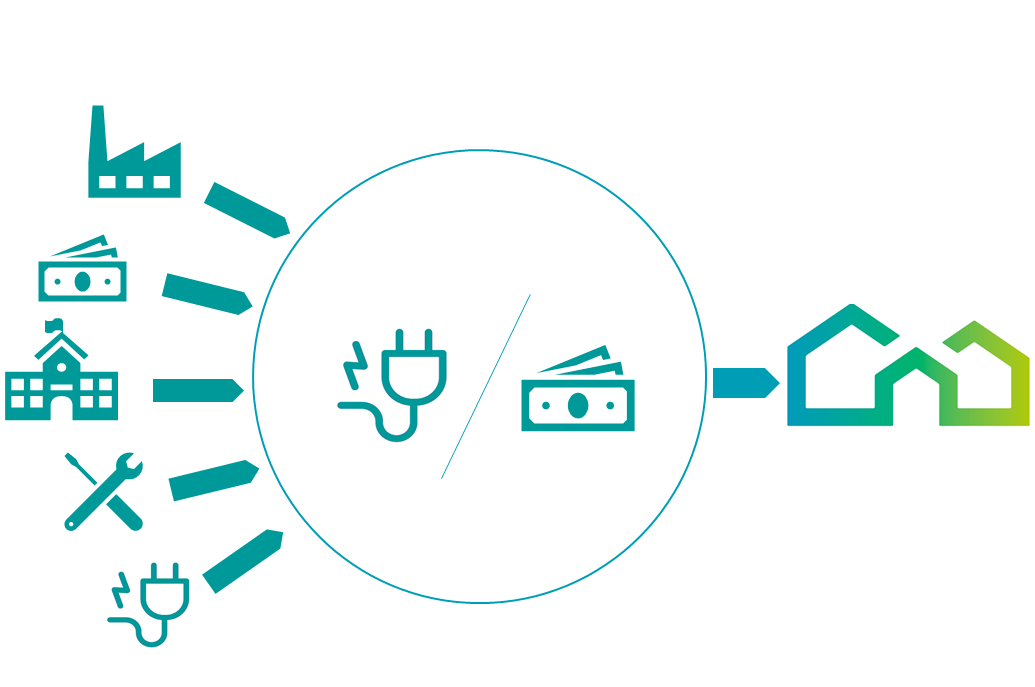

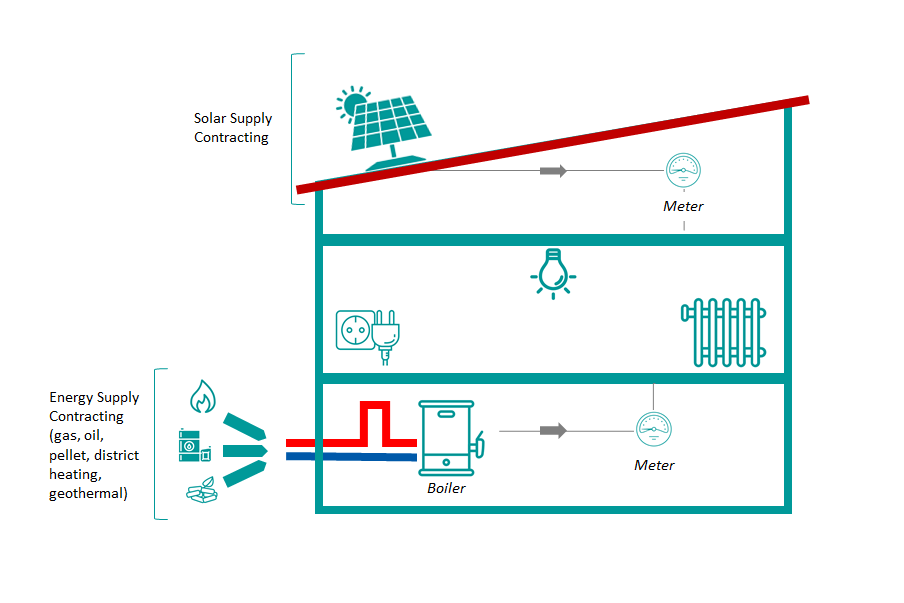

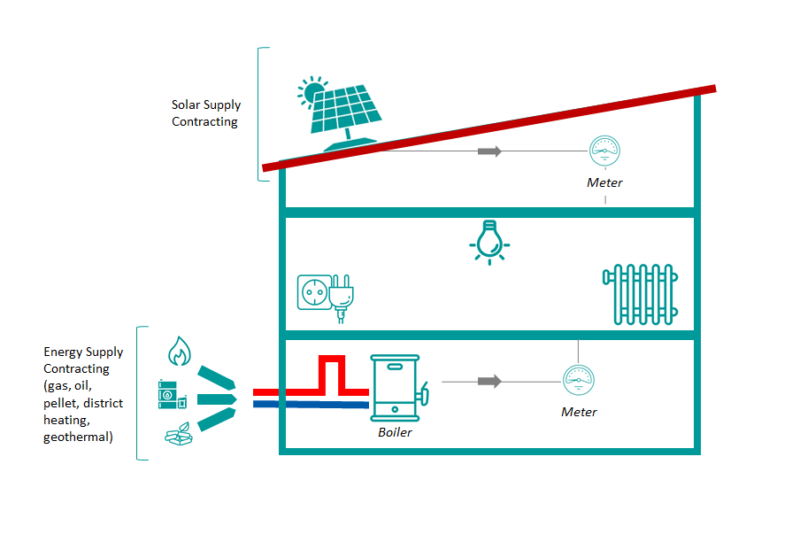

Energy Supply Contracting (ESC)

The Energy Supply Contracting (ESC) business model is a proven model to implement efficient supply (from fossil and/or renewable sources) in new and existing buildings of the public, industrial, commercial and large residential sectors. The goal is to bring a reduction of final energy demand, although efficiency gains are usually limited to the energy supply system.

Indeed, under an ESC model, an Energy Service Company (ESCO) is only remunerated for the useful energy output, i.e. it supplies useful energy, such as electricity, heat, or steam under a long-term contract to a building owner or building user. It is therefore in the interest of the ESCO to reduce the final energy demand. The output is measured and verified in Megawatt hours delivered. ESC models run under long-term contracts of typically ten to fifteen years, depending on the technical lifetime of the equipment deployed.

Extended project terms or building cost allowances allow to include measures with longer payback times, like facades with integrated PV modules or entire building envelopes. The building owner has the opportunity to outsource technical and economic risks related to energy supply activities (including planning, installation, operation, maintenance and financing of equipment for heating, cooling or electricity generation) to a professional party and to buy services instead of individual components. ESC often includes supply of final energy through the ESCO.

As the ESCO’s remuneration is performance based and depends on the useful energy output delivered, the ESC model provides an incentive to increase the efficiency of the energy conversion and to reduce primary energy demand. Contract covers the outcome and all costs of the services, as well as the commercial, technical and operational risks of the project. ESC may accelerate the uptake of Renewable Energy Technologies (RET) if they are cost competitive over the lifecycle of the project because ESCOs have an inherent interest to reduce life-cycle costs.

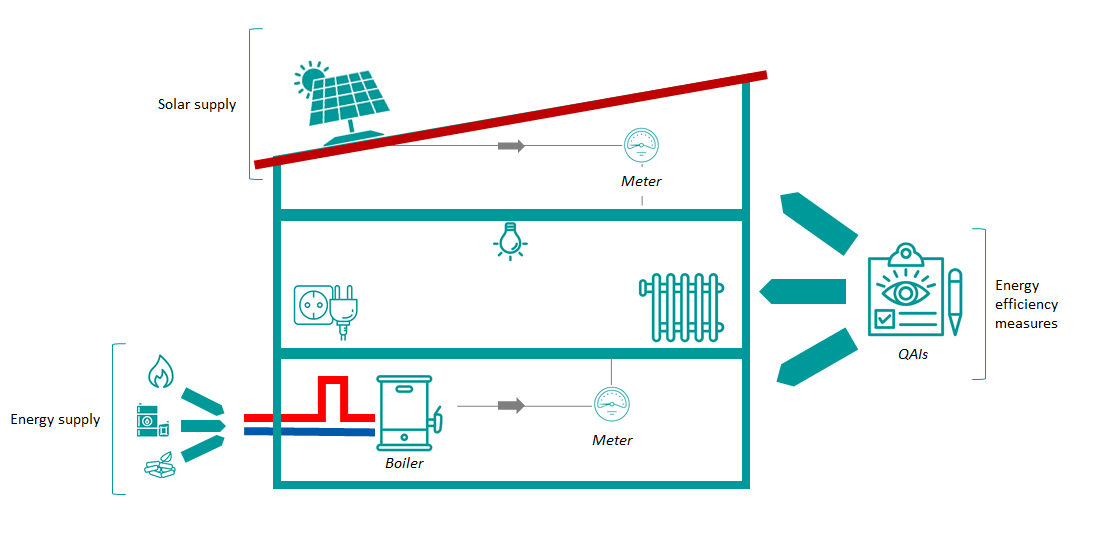

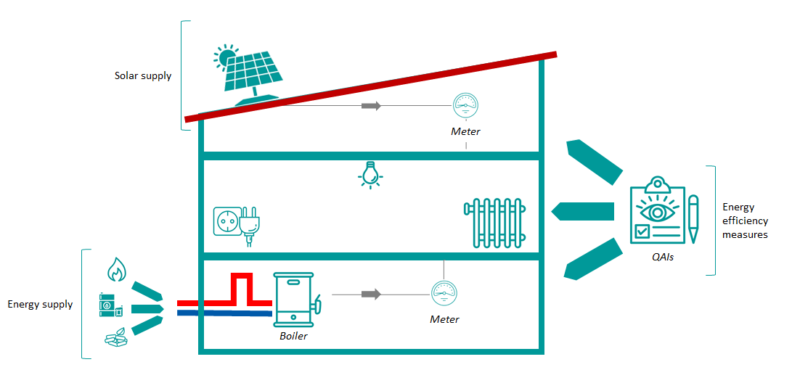

Integrated Energy Contracting (IEC)

The Integrated Energy Contracting (IEC) business model is a hybrid of Energy Supply Contracting (ESC) and Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) which combines two objectives:

- Reduction of energy demand through the implementation of energy efficiency measures in the areas of building technology (HVAC, lighting), building envelope and user behaviour;

- Efficient supply of the remaining useful energy demand, preferably from renewable energy sources.

It is methodologically based on the ESC model and is supplemented by a “deemed energy savings” approach regarding energy efficiency measures. Compared to standard ESC model, IEC model extends the range of services to the energy and emission savings potential for the whole building, with support of Quality Assurance Instruments (QAIs).

Deemed savings are a specific approach to estimate energy and demand savings, used with programs targeting simple efficiency measures with well–known and consistent performance characteristics. Basically, this method involves multiplying the number of installed measures by an estimated (or deemed) savings per measure, which is derived from historical evaluations. This approach replace the potentially complex and costly measurement of energy savings undertaken in the EPC business model. Therefore, IEC reduces transaction costs, especially for small projects.

As compared to standard ESC, the range of services in IEC model is extended to the overall building or commercial enterprise, so the offer is not limited to heat supply. Instead, the model is intended to be used for all energy carriers such as heat and electricity, but also other consumption media such as water or compressed air.

As with ESC and EPC, the IEC business model offers the building owner the choice to outsource technical and economic risks, associated with the implementation of Renewable Energy Technologies (RET) and energy efficiency measures, to a professional third party and buy services instead of individual components. IEC may be particularly suitable to combine supply from renewable sources with energy conservation measures, and thus accelerate RET adoption.

Basically, the IEC business model benefits from the ESC with similar price components, and it is supplemented with a flat rate price for the energy efficiency measures. Individual QAIs for the installed energy efficiency measures secure the functionality and performance of the measures, but not their exact quantitative outcome over the entire project cycle compared to EPC tools. The objective is to simplify the business model and to reduce (transaction) cost by balancing measurement and verification cost and accuracy. Appropriate QAI’s need to be defined for each energy efficiency measure, e.g. a one-time performance measurement for a new street lighting or a one-time thermographic analysis for verifying the quality of a refurbished building envelope. These QAIs replace the annual measurement and verification of the EPC savings guarantee.

Add-on Business Model

The Add-on Business Model is a renovation strategy corresponding to the construction of one (or a set of) additional building unit(s) – like aside or façade additions, rooftop “vertical” extensions or even a new side-building construction – that are added to the existing building when performing renovation works.

When combined with the adoption of EE or RET measures, volume additions are interesting types of intervention since they instantly produce new,  commercially valuable dwelling areas which could compensate the costs of energy-optimisation (thanks to the sale or the rent of the new dwellings).

commercially valuable dwelling areas which could compensate the costs of energy-optimisation (thanks to the sale or the rent of the new dwellings).

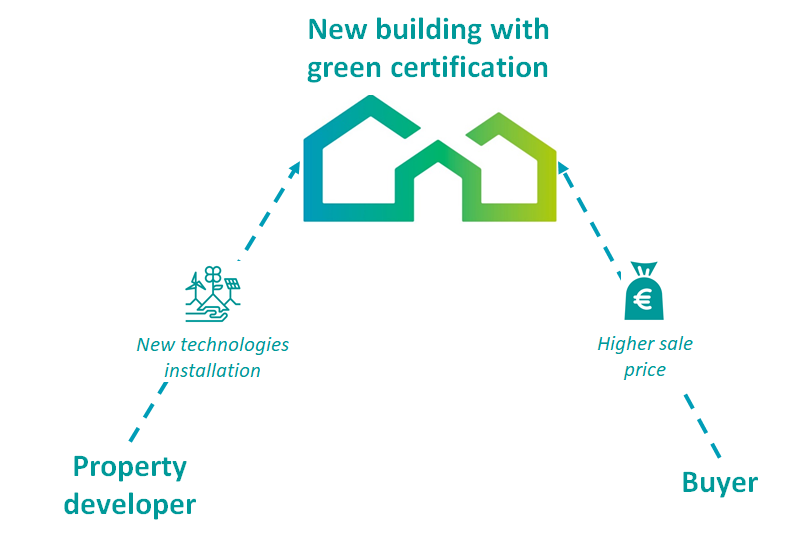

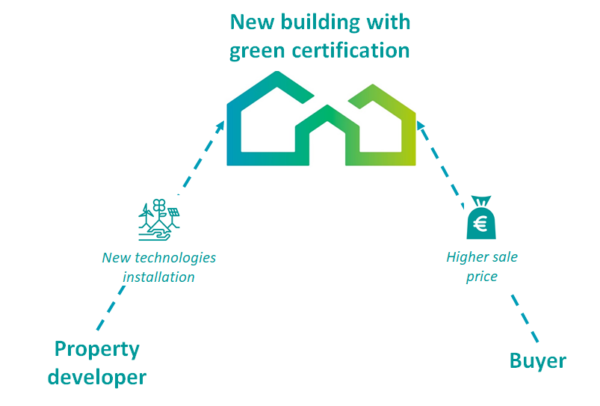

Properties certified with green building label

Green building certification systems assess a building’s performance based on environmental and wider sustainability criteria and provide the evidence that building procures a certain sustainability standard. Green certification can stimulate investments in renewable technologies, even when they are not cost-effective. However, it is generally efficient in niche markets because such certification is on a voluntary based.

In this business model a property developer or architect designs and builds buildings certified according to a voluntary green certification scheme, expecting to realize a sales/rent price premium compared to conventional buildings. This is frequently the case in the North American and some Asian markets.

This premium should compensate for the additional costs related to the green features of the building, and for the costs of the certification.

Drivers for an increasing demand for certified buildings include:

- Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): green buildings are part of their green image;

- Reducing operating costs of green buildings

- Enhancing levels of comfort for building users, which in commercial buildings may lead to higher productivity and less sick leave;

- Regulation which mandates green certification, for example for public buildings, and turns voluntary schemes into mandatory ones.

Most green building certification systems cover a range of environmental and broader sustainability criteria related to energy and water uses, indoor environment and materials used. Some systems also include criteria on functionality and comfort, economic questions and innovation. Normally, a building must fulfil most of the criteria set by the certification systems.

There are a variety of voluntary certification systems globally. The most widely used are the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED standards and the UK based ‘Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment’ (BREEAM). There are also schemes which focus exclusively on energy related criteria, e.g. the U.S. and Canadian Energy Star label for buildings, the German ‘Passive house’ standard, the French ‘Haute Qualité Environnementale’ (HQE) stardard and the Swiss ‘Minergie’ standard.

In addition to certification systems, there are also building rating systems, which do not issue a formal certificate. These rating systems support project developers by setting clear standards on what constitutes a green building. As rating a building is cheaper than undergoing a formal certification process, rating systems are frequently used for residential buildings.

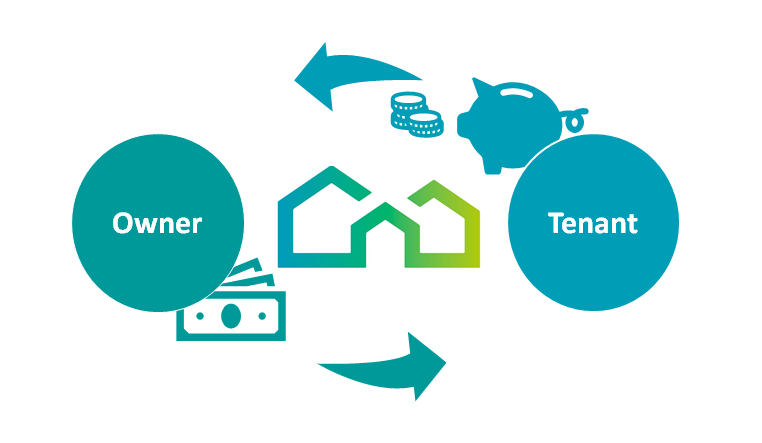

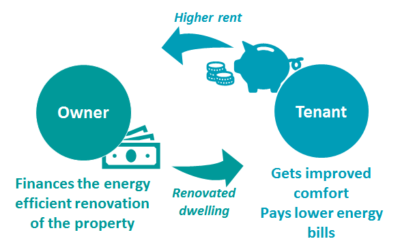

Financing through rent increase

Building owners who do not occupy a building themselves or housing corporations can profit from additional revenue opportunities after undertaking investments for energy efficient measures if they are allowed to charge higher rent from their tenants after the renovation. The higher rent takes the tenant’s energy savings into account. This helps overcome the barrier of split incentives, i.e. the lack of incentives to realize building improvements when owner and occupant are different parties.

This business model is based on a regulation that allows such rent increases and is being introduced in a number of countries. Such regulation is possible in situations where a legislation on maximum rents and/or maximum allowable rent increases exists. This is usually the case in the social housing sector, but it may also exist in the wider residential rental sector where buildings are owned by private persons or property companies.

As this business model is based on a change in legislation regulating the rental sector, its attractiveness for the building owner directly depends on the details of the legislation, e.g. how much of the energy savings or of his up-front investment a building owner is allowed to recover. It is unlikely that being able to charge higher rents to tenants will be the sole driver for a property owner’s decision to undertake renovation measures. However, the higher rents may still play a significant role in the decision. It is expected that in its current form the business model is mostly applied for the implementation of energy efficiency measures which are usually more cost-effective than renewable energy technologies. But theoretically the business model may also be applied for the implementation of renewable energy technologies (RET), e.g. for the installation of a heat pump which reduces energy costs for the tenant. There are only few new business models and innovative policy instruments which specifically address the barrier of split incentives. This implies that this business model, potentially supported by additional incentives, may play an important role in catalyzing energy improvements of the existing building stock in the large rental sector.

The application of the business model is limited to countries or regions that have a regulated rental sector. In this sector, mostly large property owners are active, such as social housing corporations which frequently have the long time horizon, access to capital and technical expertise required to plan and undertake renovation measures.

RentalCal is an international research project funded by the European Union under the H2020 framework. The project aims at developing a methodology for the profitability assessment of energy efficient refurbishment investments in the rental housing sector. The second objective of RentalCal aims at providing comparable and transparent information on the profitability of energy efficiency investments that can be used both for the assessment of investment decisions, and for the comparative analysis of existing barriers in the private rental housing stock of participating countries. RentalCal specifically aims to prepare the ground for investment in the existing rental housing stock, all across EU.

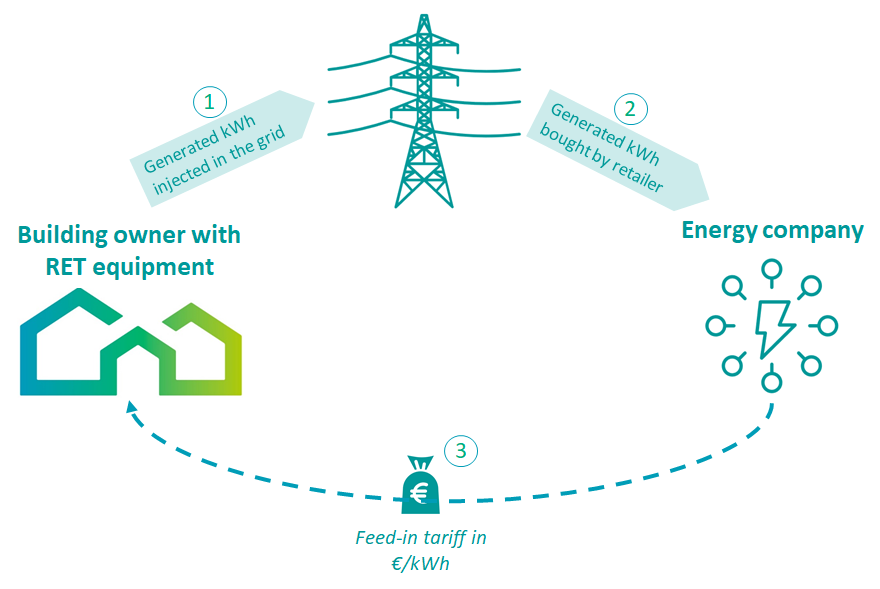

Feed-in remuneration scheme

A feed-in remuneration is a support scheme allowing the producer of renewable energy to receive a direct payment per unit of energy produced. This feed-in remuneration can be a tariff, like a preferential price covering the full generation costs, or a premium, which provides a ‘bonus’ for the producer to cover the financial gap between the generation costs of using renewable energy versus using conventional (fossil) energy.

Feed-in schemes are very efficient to increase the deployment of RET, as they cover the higher cost of RET by compensating the owner with a higher price for the renewable generation. A feed-in remuneration scheme creates opportunities for business cases as it can cover the financial gap between RET and conventional technologies. Feed-in tariffs or feed-in premiums for electricity from renewable sources are the most common, but also exist for renewable heat.

Through a feed-in remuneration scheme the producer of renewable energy receives a direct payment per unit of energy produced. A feed-in scheme guarantees access to a predictable and long-term revenue stream, which can serve as a stable basis for a business model.

In addition to the tariff scheme, in which the producer gets a fixed price for the supply of energy, and the premium scheme, in which the producer gets a premium in addition to income from selling the energy on the market, hybrid forms are also possible. In these, the premium complements the income from the market, to jointly cover the generation costs. Producer gets a fixed amount, but from two different sources. This hybrid form is similar to a feed-in tariff for the investors, but it has different consequences for government expenses. A feed-in scheme typically publishes rates per energy unit for eligible production (e.g. in €/GJ or €/kWh). If a producer is eligible, a contract (or agreement) can be obtained from the government that allows the producer to claim the specific tariff (or premium) for every unit produced. This agreement fixes the conditions and levels of the tariff, typically 8-20 years depending on the technology. So once an agreement is entered, this is virtually risk free. Some feed-in schemes only cover energy that is delivered to the grid, whereas other schemes also cover auto-production (using generated energy for own purposes).

Feed-in schemes do not look at specific projects and real costs, but instead use cost estimates per category. As a result, within a category some initiatives may be economically viable whereas others are not. To build a viable business model based on a feed-in scheme, the investor has to undertake a careful assessment of the project economics taking into consideration e.g. climate conditions for solar PV or heat pumps, technology costs, and fuel prices, e.g. prices of biomass for a biomass boiler.

In the case of building refurbishment, feed-in schemes can be used by households and small/medium enterprises who want to generate their own energy using renewable sources (e.g. solar-PV or biomass heating). Such business models by households or SMEs can be focused on production for own use, or for the sale of energy to the grid. Feed-in schemes typically differentiate in categories by size of the installation, technology and fuel used. The level of remuneration is based on the category specific generation costs (usually estimated through the size of the installation, for instance installed capacity in kWp for PV), but the actual payment is based on production (e.g. kWh of electricity).

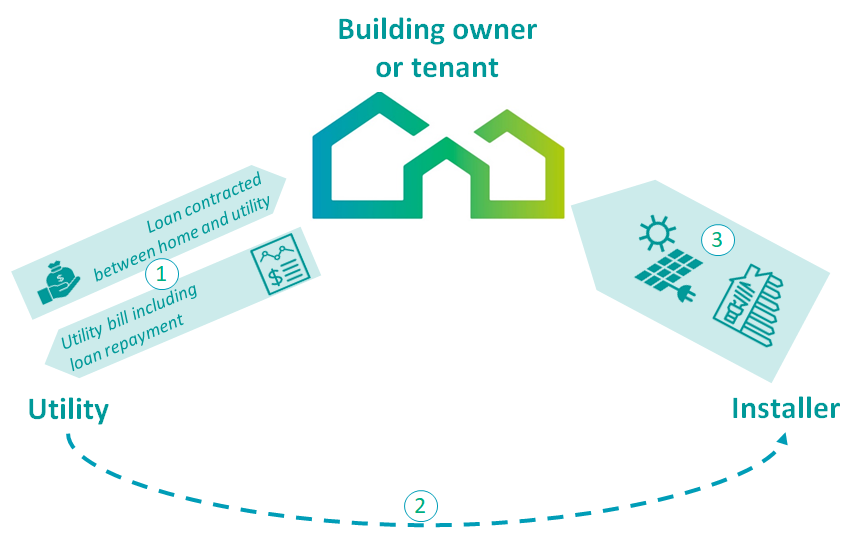

On-bill financing

On-bill financing programmes are another model to cross the barrier of high up-front costs and access to capital. A utility provides capital to a home-owner for the installation of Renewable Energy Technologies (RET) or Energy Efficiency (EE) measures, and refund is made through the home-owner energy bill, i.e. building owners (or building users) repay the loans through an extra on their utility bills. Preferably, the overall utility bill should still be lowered thanks to the associated energy cost savings. Also, if the house is sold, it is possible to structure the programme in a way that the loan stays associated with the utility meter and can be transferred to the new owner.

Two types of programmes exist for the on-bill financing business model:

Two types of programmes exist for the on-bill financing business model:

- With an on-bill loan programme, a personal loan is issued to the building owner, repaid as a specific item on the utility bill (repayment periods are often set at around 5 years). However, it is legally not linked to the property or the utility meter;

- In on-bill tariff programme, the building owner also repays the loan via the utility bill (repayment periods are often set at around 10 years), but in this case it is considered as an ‘essential service’ and own part of tariff. The obligation for payments stays with the property and is transferred to the next owner in the case of sale of the property.

Generally, the target for the investments in RE and EE measures is to generate positive cash flows for the property owner, so repayment periods vary depending on the expected energy savings and the useful life of the installed measures.

In the on-bill financing business model, the utility does not only administer the programme and collect payments via electricity bills, but it also finances the investments from its own capital.

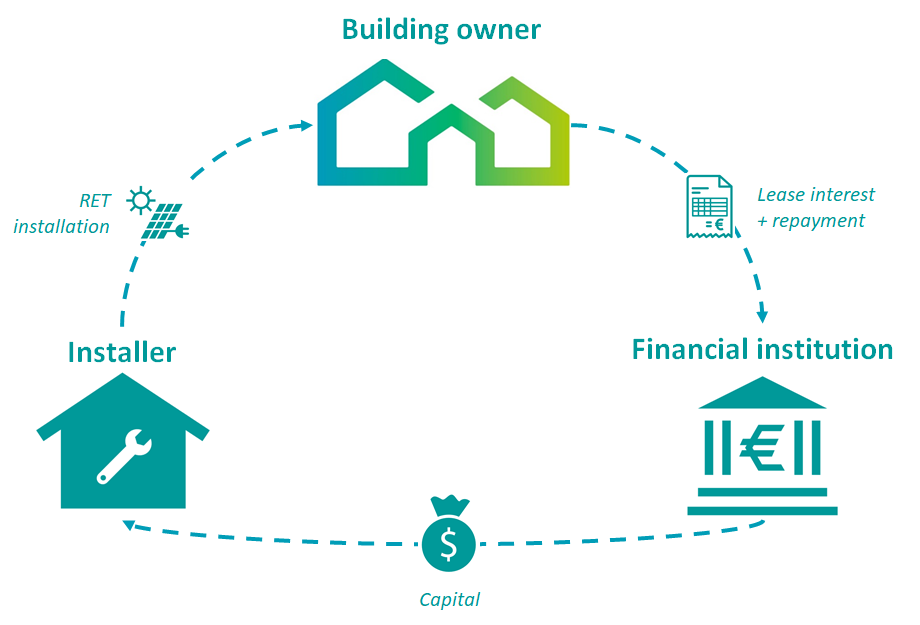

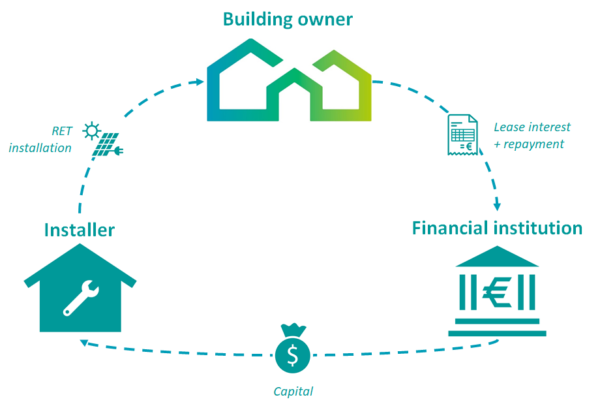

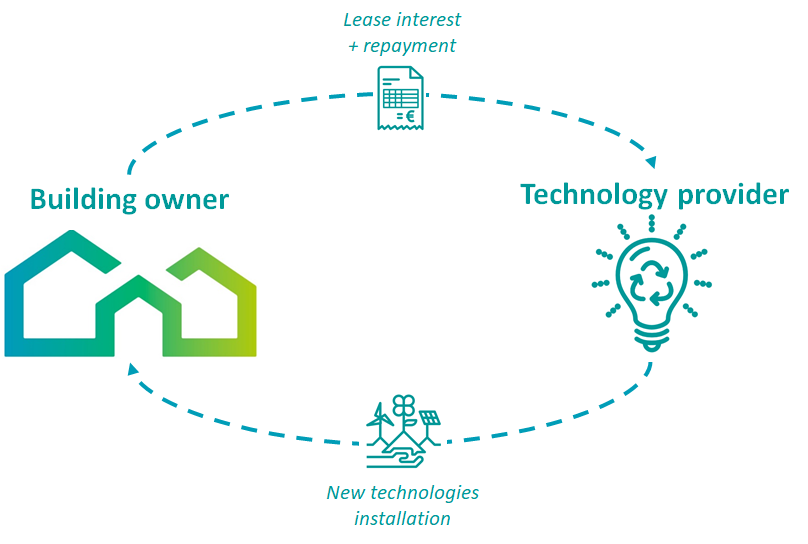

Leasing of Renewable Energy equipment

Leasing enables a building owner to use a renewable energy installation without having to buy it. The installation is owned or invested in by another party, usually a financial institution such as a bank. The building owner pays a periodic lease payment to that party.

This business model consisting in leasing Renewable Energy Technologies (RET) offers new opportunity for building owners to use RET without having to make an upfront investment. It is applicable to large scale equipment in commercial buildings and in some cases to small-scale devices for private home owners, for instance RET such as photovoltaics. The opportunity to lease equipment may be part of an energy services package offered by an Energy Service Company (ESCO), but may also be offered on its own, especially in the case of individual residential customers. In addition to RET, leasing may be available for energy equipment and installations like condensing boilers, small and micro-CHP systems.

Generally, the actor who offers the lease (i.e. the lessor) remains owner of the asset during the lease period. However, several types of leasing are possible, which differ in ownership and other economic, legal and fiscal conditions. There are two main types of leases: operational lease (or operating lease, usually treating as renting) and financial lease (or capital lease, usually treated as a loan. In that case, there is a an ownership transfer option at the end of the lease period).

Leasing can be a central component of the business model of an ESCO having limited own capital (and therefore limited access to debt), which in this case may lease equipment from a financial institution. The ESCO then installs the equipment at the premises of its customers as part of the services that it offers. However, building owners may also finance RET via leasing without the involvement of an ESCO.

Leasing can also be a central component of the business model of a company that introduces a specific new technology to the market. Company providing the technology can offer it to property owners via a leasing arrangement, including a service and maintenance package.

In brief, the different scenarios can be illustrated as follow:

- A bank acts as the lessor of RE equipment. The building owner leases – for instance – a solar water heater directly from a bank, which owns the equipment. In exchange the building owner pays a periodic lease rate during the contract period which includes a lease instalment and interest share:

- An ESCO undertakes the negotiations with the financial institution, provides additional services to the building owner and acts as the tenant of the equipment, which is still owned by the financial institution. The advantage of the involvement of an ESCO is that the ESCO can act as a facilitator:

- A provider of a specific technology, such as a micro-CHP system, leases the system to private or commercial customers. This approach is mostly used by companies who want to bring a new technology into the market, and must compete against established technologies, traditional institutional areas of influence and potentially long supply chains to individual customers. The technology provider usually also provides operation and maintenance services for the equipment:

Leasing is however not frequently used for RET (and even less for EE solutions). One reason for this is that not all RET can be leased. Generally, any equipment totally integrated in a building has to be owned by the building owner. If installed technologies become part of the building, an operational lease is impossible because for this type of lease the ownership has to remain with the lessor. Another reason is that regulation usually requires that after the leasing period, an asset can be reused in reasonable state at a different time and place. This criteria is referred to as ‘fungibility’. RET systems such as soil or water-based heat pumps do not meet this criteria as the complete system cannot be removed without substantial damage. Similarly building insulation, which is often a very suitable energy efficiency measure, cannot be removed after the end of the lease term.

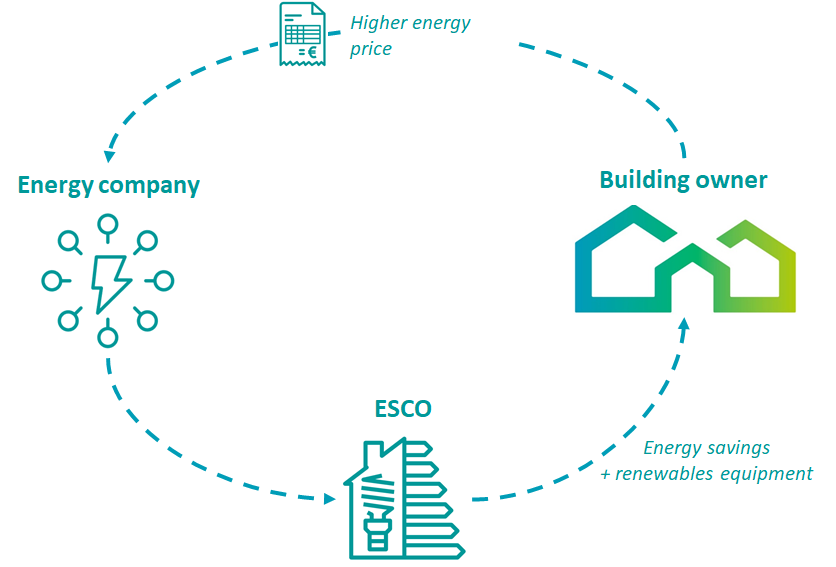

Energy Savings Obligations

Energy Saving Obligations are a policy tool obliging energy companies to implement and realise energy savings at the level of end users. It stimulates business models with financial incentives offered by energy suppliers to building owners, renters or energy service companies.

Innovative financing options can also emerge under energy saving obligations for utilities. The utility (potentially via an Energy service company or ESCO) proposes incentives for energy efficiency investments, financed through higher energy prices. These incentives offer opportunities for building owners. Despite first intention oriented to energy savings and energy efficiency, energy saving obligations could also be an important driver for renewable energy technology in the built environment.

Innovative financing options can also emerge under energy saving obligations for utilities. The utility (potentially via an Energy service company or ESCO) proposes incentives for energy efficiency investments, financed through higher energy prices. These incentives offer opportunities for building owners. Despite first intention oriented to energy savings and energy efficiency, energy saving obligations could also be an important driver for renewable energy technology in the built environment.

Energy Saving Obligations stimulate energy companies to develop new energy efficiency services for final customers (often in partnership with electricians and installers), or they outsource the obligation and delegate it to the ESCO. Generally, in this business model, energy companies transfer the costs of the energy efficiency measures (and potentially renewables) to final consumers, through higher energy prices.

Energy companies, or ESCO partners, need to create financial incentives for consumers to voluntarily implement energy savings in buildings. For instance, in Italy, France or UK, subsidies for saving measures are the most common financial incentive. In order to be able to finance the incentives offered, energy companies are generally allowed to charge higher energy prices to all customers. In many cases, financial incentives for energy consumers are combined with information to encourage energy efficiency measures.

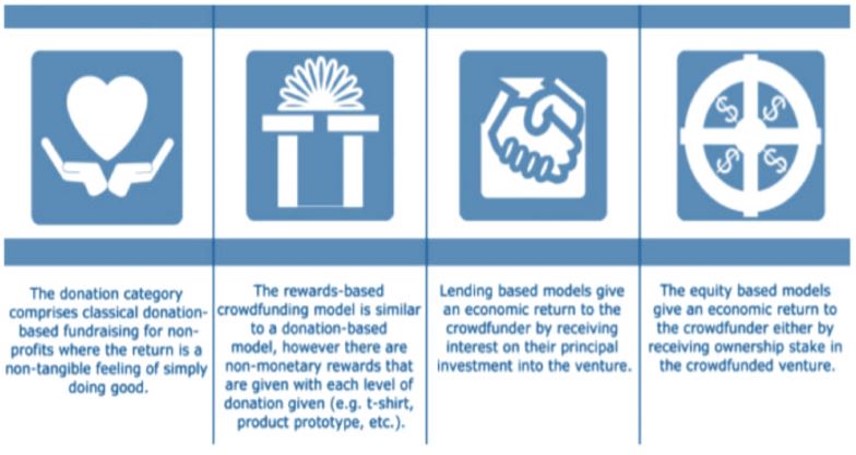

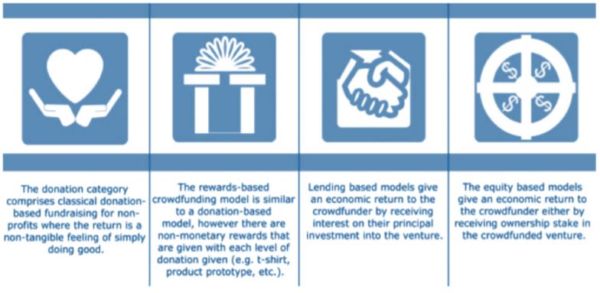

Crowdfunding model

Crowdfunding approach is an alternative method, completely different to the common typical business process, used to raise capital through small collective efforts (amounts of money) of a large number of people, friends, family members, customers and individual investors, and finance a project. In particular, it allows to know about a business even before it is launched, and is based on a network of people. Large investments have to be planned using multimedia information systems (text, audio, images, video, animations, …) that should persuade investors (no banks or other institutions involved) without providing guarantees of the business plan.

Nowadays, the crowdfunding for real estate sector is only applied to the U.S. market. In Europe, crowdfunding for real estate projects is not allowed yet, but there are various platforms that are already using the concept in different ways (e.g. banks are involved in this business and the amount of the investment is limited). Italy is an example of this approach, and even if it has been the first country to introduce a legal framework regarding equity crowdfunding, the market is still waiting for some changes in order to be as efficient as in the US.

The Crowdfunding scheme until now has been used to finance a wide range of projects in different fields, such as art, scientific research, medical, travel, social, civic projects, and only recently has been applied to renovation and the energy efficiency sector.

Crowdfunding can be classified into four different models, according to the revenue model as explained in the following figure:

- Donation Based Crowdfunding

- Rewards Crowdfunding

- Equity Crowdfunding

- Lending-based crowdfunding